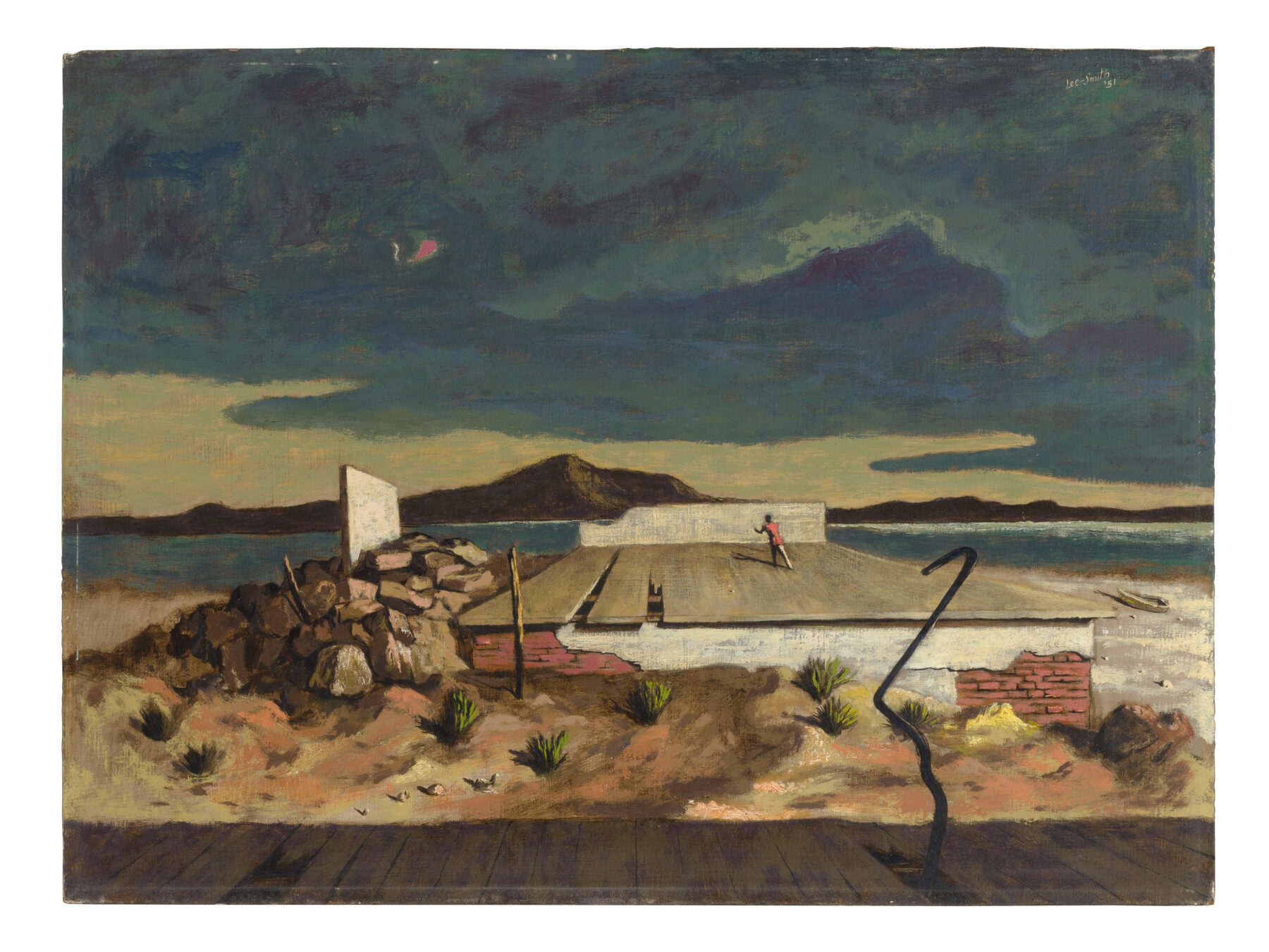

Hughie Lee-Smith

In the New York Times obituary for Hughie Lee-Smith on March 1, 1999, he was succinctly described as “…a Painter of Spare, Bleak Scenes Touched with Mystery.” Considered at the same time a social realist, romantic realist and surrealist painter, Lee-Smith was a master of subtlety, and has been compared to Giorgio de Chirico and Edward Hopper. He often implied social tensions through an atmosphere of psychological alienation in his paintings. However, the artist admitted that his works could be read with many meanings.

Lee-Smith was born in Eustis, Florida, but lived with his grandmother in Atlanta after his parents divorced. When Lee-Smith was ten, he moved to Cleveland to join his mother. She recognized his talent and passion for drawing and enrolled him in classes for gifted children at the Cleveland Museum of Art. He later studied at the Cleveland Institute of Art, graduating with honors in 1938. With his degree, Lee-Smith taught at a center for black artists and began to exhibit his own works. In 1941, Lee-Smithmoved to Detroit, a transition that was interrupted by the war. After serving in the navy as a mural artist, he returned to Detroit and obtained a degree in Art Education from Wayne State University in 1953. In conjunction with his teaching, Lee-Smith actively painted and exhibited his works throughout the decade and won a top prize for painting from the Detroit Institute of Arts in 1953. In 1958, Lee-Smith moved to New York. He taught at the Art Students League for 15 years from 1972-1987. In 1963,he was elected an associate member of the National Academy of Design, only the second AfricanAmerican member to be named (after Henry Ossawa Tanner in 1927). He became a full member in1967. Despite this recognition, it was not until 1988 that a retrospective of his work was held, organized by the New Jersey State Museum.

The foundation for Lee-Smith’s career and characteristic style was established when he lived in Detroit from 1945 until 1958. During this period, Lee-Smith eloquently addressed the plight of American youthin many of his paintings. The loneliness and isolation of the stark, run-down urban landscapes or seaside environments in which he places people is palpable. Having lived in blighted areas in Cleveland and Detroit, Lee-Smith understood life in neglected neighborhoods. He made sketches among the demolitions for the Detroit Expressways, incorporating them into several works in his solo show at the Detroit Artists Market in 1952. Despite the pervasive loneliness of his works, sometimes an uplifting emotion is conveyed in the expression of a child or the soft and light rendering of his skies. Memories from his childhood also surface in his art, particularly in the form of carnival imagery—colorful balloons, fluttering ribbons and stage-like settings.

The present work, Untitled, is an important work from this time period. The spare, desolate scene is set on a rocky lake shoreline, probably in Michigan or Ontario. The silhouette of a mountainous region and clouds resembling biomorphic forms recedes into the background, recalling the nocturnal seascapesof American tonalist Albert Pinkham Ryder, an influence for Lee-Smith. A womanstands on a decrepit wooden pier that has cracked and eroded with time, the white plaster façade of the base crumbling to reveal the red brick foundation. A humble wooden rowboat is docked on the shore awaiting the return of the lone woman. Anchoring the left side of the composition is a pile ofboulders with a concrete slab emerging like a gravestone. Juxtaposed with this portentous symbol is a woman reaching towards a soaring red kite above, untethered by its tail. Unlike the heaviness and enormity of the rocks and wooden planks, the woman is painted as a minuscule figure, with a delicate lightness in her body and gesture.

Reflecting Lee-Smith’s training as a stage set designer, Untitled appears as a dreamlike theatrical production with the woman staged like an actor on an expansive wooden stage, and the intenselight that bathes the scene, casting long, dramatic shadows. Perhaps the scene is a metaphor for hope, reflecting the artist’s optimism in spite of the emptiness and decay. The mood is further defined by the strange angular black wire in the foreground, a signature element in many of Lee-Smith’s paintings. The rarity of this work lies not only in the subject matter and the artist’s unique style, but that it remained in one family since 1952. The work was in the collection of Louis Redstone, a prominent modernist architect in Michigan.

Lee-Smith’s style and subject matter were remarkably consistent throughout his seven-decade career. In a credo he wrote on May 15, 1945, while he was serving in the Navy, he explained: “…if art is to survive it must express the needs and aspirations of the people and solidify them in the struggle for the achievement of their political, social and economic goals. If art is going to be effective in this social task it must be understood. Form and style must, therefore, meet with the approval of the great majority of people. Unless the artists takes into consideration the art-understanding of the common man, I am afraid he is imposing art from above; art that is uncalled for and unwanted” (Archives of American Art, Hughie Lee-Smith papers, 1942-1980, Reel 69-11, Frame 15). Lee-Smith’s ability to relate to his audience made him an influential, if not overlooked, realist painter of the 1940s and 1950s.

Hughie Lee-Smith

Untitled, 1951

Oil on masonite

18″ x 24″

Signed and dated upper right

Provenance

The Artist

Louis G. Redstone, Detroit, Michigan, acquired from the above in the early 1950’s

Private Collection, by family descent from the above

Private Collection, California, acquired from the above in 2020