Bill Traylor

Essay from the Smithsonian American Art Museum website:

Bill Traylor was born around April 1, 1853, on the Alabama plantation of John Getson Traylor in Dallas County, near the towns of Pleasant Hill and Benton. Traylor and his siblings were born enslaved, as their parents had been. John Getson Traylor had died before Bill Traylor was born, but his brother, George Hartwell Traylor, kept the Dallas County plantation running, holding the enslaved people there as workers and as inheritance property for John’s children, who at the time were too young to inherit. In 1863, George Hartwell Traylor–apprehensive about President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation–moved Bill Traylor (then about ten) and his family to his own plantation in nearby Lowndes County. When Emancipation became a reality in the South two years later, Bill and his family remained on George Traylor’s land as laborers.

Records for African Americans born in antebellum America are scant but indicate that Bill Traylor had three marriages, two legal and one common-law, occurring in 1880, 1891, and 1909. By 1910 he and his family (some fifteen children from those three relationships) had left Traylor land for good and were living on the outskirts of Montgomery, working as tenant farmers. His third wife, Laura, died in the mid -1920s, bringing Bill Traylor’s farm- and family life to a close. By then, most of his children had joined the Great Migration and left the South. Around 1927 or 1928, Traylor moved to Montgomery on his own. Except for brief stints with his grown children in Detroit, Philadelphia, and Washington, DC, before and during World War II, he remained in Montgomery until his death on October 23, 1949.

Traylor is known today through the large body of drawn and painted work he made during his years living in the Alabama state capital. In the segregated part of Montgomery, Traylor found work and lived successively in several different places. After about a decade there, Traylor’s strength declined, and he took to sitting in the neighborhood around Monroe Street, drawing by day and lodging by night with local business owners. His earliest extant drawings date to 1939 and were primarily done in pencil or colored pencil. Traylor’s artworks were saved by several members of a white artists’ coalition in Montgomery called the New South. Notable for the help they gave Traylor, in acquiring and saving artworks, and taking documentary photographs are John Lapsley, Jay Leavell, Ben Baldwin, Blanche Balzer and Charles Shannon (who would marry in 1944), Jean and George Lewis, Mattie Mae and Paul Sanderson, and several others. Charles Shannon saved the lion’s share of Traylor’s art and was instrumental in bringing Traylor and his work to the attention of a larger sphere several decades after Traylor’s death. The New South mounted a small show of Traylor’s art in Montgomery in February 1940, but it was the Corcoran Gallery of Art’s 1982 traveling exhibition Black Folk Art in America that brought Traylor’s work lasting and widespread attention.

Traylor drew and painted, mostly on discarded pieces of paperboard from the neighborhood, from around 1939 until shortly before his death in 1949. His images attest to his existence and point of view; they describe his memories of a hard, rural, racially fraught past, as well as the evolving African American urban culture that was taking shape before his eyes. Traylor never became literate, but his pictures became a language unto themselves. His visual depictions are steeped in a life of folkways: storytelling, singing, local healing, and survival. As these modes of expression are well known to do, Traylor’s imagery often holds veiled meanings and lessons underneath the veneer of simplicity or hilarity. Traylor became adept at creating pliable narratives; he experimented with allegory and abstraction and was able to convey a volume of meaning in deceptively simple images. The racial terrorism of lynching peaked between 1877 and 1950–Traylor’s adult lifetime. It was illegal, but in Jim Crow America it was rampant, and far too often, tolerated or endorsed. His abstracted “stages” are skeletal references to Montgomery, echoes of a building or fountain, but perhaps also an auction block where human beings were once sold as goods in the heart of the city’s Court Square, a few blocks from his environs on Monroe Street. Traylor’s complexand coded scenes evidence the balancing act that defined life not only for his community, but also for Traylor personally, as he tried to record these memories without drawing attention to himself for doing so. World War II interrupted Traylor’s interaction with the Montgomery artists who had supported him and collected his work. He visited his children in the North and East, and left the black business district. Returning to Montgomery, he lived for a time in a shanty overlooking the Alabama River; after 1945, he went to live with a daughter who resided in town. Between 1942 and his death, Traylor did make art, and although some images from this period were saved initially, none of them seems to have survived. Traylor died in 1949, impoverished and in the squalor of a segregated hospital. He was buried on the outskirts of town, in a grave that had gone unmarked until March 2018.

Posthumously, Traylor became celebrated as an accidental modernist, whose somber silhouettes compress a universe of volume and feeling into the flattest of shapes. But Traylor’s aims were never those of the art world. He came to art making on his own and found his creative voice without guidance. His works are neither straightforward “memory paintings” nor realistic depictions from life. In fact, Traylor was a careful editor; he chose his subjects with specificity and he omitted a great deal. When Traylor started drawing, it was a radical act. He was among the first generation of blacks to become American citizens, but literacy and personal agency for African Americans were still touchy issues in Alabama–and personal expression poking at a racially fraught past was unequivocally dangerous. Social systems in the Jim Crow South–designed to impoverish and disenfranchise the formerly enslaved–were forceful and pervasive, and Traylor’s existence was grounded in knowing the difference between white and black worlds and keeping his thoughts and personal views hidden. But for Traylor, charting his life and memories in pictures was an indelible and validating testament of selfhood, and in their very creation are subversive works.

Traylor’s body of work is artistically unique, but its historical position is singular as well. No other artist captured the complex, drawn-out moment between slavery and civil rights. It remains the only substantial surviving body of drawings and paintings by a man born into the ruthless but then-dying system of American slavery.

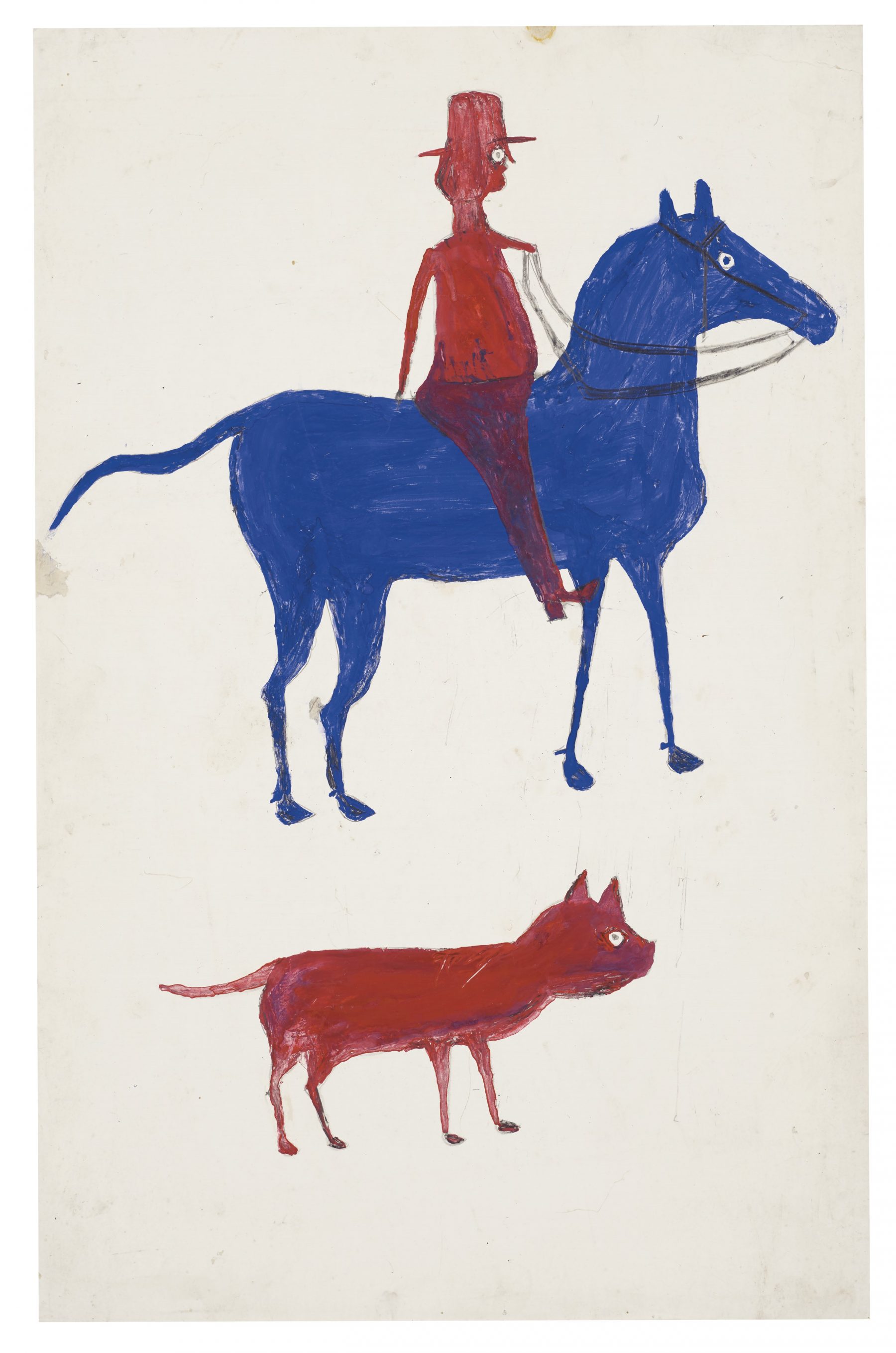

Bill Traylor

Red Man on Blue Horse with Dog, 1939-1942

Oil on canvas

22″ x 14 1/2″

Provenance

Ricco Maresca Gallery, New York

William Louis-Dreyfus, Mount Kisco, New York, 1991, acquired from the above in 1991

Acquired by the Louis-Dreyfus Family Collections by inheritance from the above in 2016 Christie’s, New York, January 17, 2020, Estimate $150,000-250,000, solf for $325,000

Private Collection, Michigan, acquired from the above sale